Opening of the exhibition "Under Occupation"

On May 14, in the Vukovar City Museum we opened the exhibition Under Occupation. Ukrainian artists respond to the trauma and destruction of cultural heritage. The exhibition is a powerful tribute to those who survived, fled, or remained under occupation, as well as to those who lost their lives in the Russian war against Ukraine. Presenting the works of five artists from the period 2014 to 2025, the exhibition depicts the full scope of the war in Ukraine through documentary comics, photographs, collages, graphic stories, animated video works, and installations.

The stories behind the art

At the beginning of the war, in 2014, pro-Russian forces captured Slava Bo (Vyacheslav Bondarenko), a cultural manager from Luhansk, and subjected him to severe torture. Despite the ordeal, he managed to survive and escape to the territory controlled by Ukraine. In his triptych Slava Bo, Displaced he delves into the deep question of what remains of a person after forced displacement. Through his work, the artist reflects on the life of an internally displaced people in Ukraine - the abandoned home, the hometown and its streets overgrown with apricots, the warmth of the steppe and colorful underground art. Slava Bo reflects on a reality where friends have scattered around the world, often leaving their identities behind. After escaping from the occupied region, Slava Bo found himself in a new environment, where he directed his energy into publishing a magazine dedicated to contemporary art, representing the cultural essence of the eastern regions of Ukraine.

Before the full-scale war broke out, it quickly became clear that many cities in southern and eastern Ukraine were at risk of falling into enemy hands. In response, human rights activists, including Yaroslav Minkin, the curator of the Under Occupation exhibition, who himself had to flee Luhansk in 2014, reached out to artists and activists they knew in the frontline areas. Their message was clear: “We believe in a brighter future and hope that nothing terrible will happen. However, as tensions remain and enemy forces are still near your cities, we warmly invite you to the STAN resource center, located in a safer region of Ukraine. Here you can rest, devote time to your creative aspirations, and confidently plan for the future, rather than anxiously awaiting what tomorrow may bring.”

When the unthinkable happened - a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine - Mashika Vyshedska and her family were already on a train heading west, seeking refuge in the foothills of the Carpathians. As displaced persons from Luhansk, they fled Bakhmut with their two young children, knowing that they could not endure occupation for a second time in their lives. After settling in the safety of Ivano-Frankivsk, the artist channeled her experiences into the animated film My Home and the war comic strip These 8 Years, sharing her story of resistance and survival.

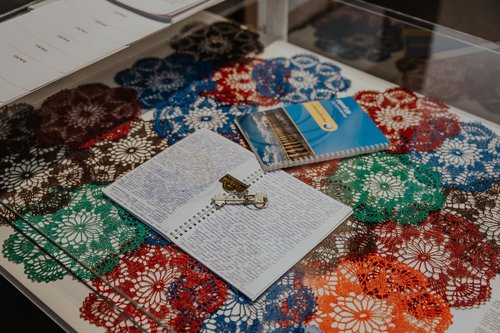

Yana Malyha, a writer from the Kherson region, decided to stay in her home on the left bank of the Dnieper River, despite the growing dangers. Her family in Novaya Kahovka, along with many others, continued to live under occupation. Yana and her daughters endured immense hardship, passing through more than 40 enemy checkpoints to escape, after two months of danger and hunger. They eventually reached liberated territory. Throughout this ordeal, Yana secretly carried with her the diary My Dead Spring, which would have cost her severe punishment from the occupying authorities if it had been discovered. This harrowing journey highlights the resilience and courage of individuals like Yana, who risked everything to preserve their stories and seek freedom. Her experience underscores the broader struggles faced by many in the occupied regions, where personal stories become acts of defiance against oppression.

For many, escape attempts ended in failure. A young activist from the Luhansk region experienced this firsthand when the bus she was travelling on was attacked and her sister was injured. Forced to return to occupied Starobilsk, they survived six months of constant danger before fleeing again – this time through Russian territory to Lithuania and Poland, before finally returning to Ukraine. There are countless similar stories, and Yana Malyha began collecting these harrowing accounts from the earliest days of the devastating war. She secretly passed them on to Yaroslav Minkin and Mashika Vyshedskaya, whose collaboration resulted in a powerful collection of graphic stories, Kherson Stories of Occupation, which documents testimonies of Russian war crimes in Ukraine. This narrative highlights the resilience of those who risked everything to escape the occupation and the courage of individuals like Yana, who worked tirelessly to preserve these stories as testimonies of the crimes suffered by countless Ukrainians.

Photographer Ksenia Yanko, originally from Poltava, was among the millions of Ukrainians forced to flee the war. From Ukraine, she traveled to Germany, where she encountered a context in which Ukrainians were often reduced to roles as hotel workers, office cleaners, and workers performing undervalued, invisible work. Before the full-scale invasion, Ksenia was deeply involved in the creative industries, advocating for the reintegration of veterans and raising the visibility of human rights organizations. The journey took her to Lisichansk, where she documented a group of enthusiasts who sought to revitalize their city on the front lines. Her photographs aimed to show the underground art that flourished in abandoned industrial spaces near the front lines. Today, her work, Lisichansk Occupied Future, is a powerful archival phenomenon—a compelling collection of photographs that document the occupation and destruction of the city in 2022. This story not only depicts Ksenia’s personal journey, but also highlights the resilience of Ukrainian communities and the lasting impact of war on the cultural and urban landscape. Her work serves as a testament to the creativity and determination of those who continue to rebuild and resist amidst destruction.

Originally from the border town of Shostka, artist Viktoriia Saryozhavna grew up intimately familiar with loss. When her hometown came under siege in 2022, she fled to the far western border of Ukraine, joining millions of internally displaced people who were forced to flee their homes. Her journey took her through a series of cities, where she grappled with the challenges of finding housing, work, and a renewed sense of identity. In her collaborative series Form of Absence, co-authored with Slava Bo, Viktoriia explores themes of loss, memory, and lived experience—elements that resonate deeply with displaced Ukrainians around the world, offering them a framework for finding new meaning in their uprooted lives. This narrative represents Viktoriia’s personal experience of war and reflects the journey of those seeking to rebuild their lives amidst uncertainty. Her work serves as a moving reminder of the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Exhibition Opening

At the beginning, the artists introduced themselves and their works that make up the exhibition. Their works depict deeply personal stories of survival – of fleeing under shelling, crossing enemy checkpoints and rebuilding lives in foreign countries.

Later, the participants had the opportunity to talk to the artists and a witness from Vukovar, the executive director of the European Centre Vukovar, Dijana Antunović Lazić, who shared with them their personal stories related to the experience of war, war trauma, but also thoughts about the future and answered numerous questions.

The exhibition can be visited until May 31st in the Orangery gallery of the Vukovar City Museum.

The exhibition "Under Occupation" is organized as part of the project Responding to Trauma and Destruction of Cultural Heritage, funded by the European Union under the Creative Europe Programme. The exhibition is organized by the association СТАН \ STAN from Ukraine, in partnership with Documenta - Center for Dealing with the Past and the Vukovar City Museum.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Executive Agency for Education and Culture (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor the EACEA can be held responsible for them.